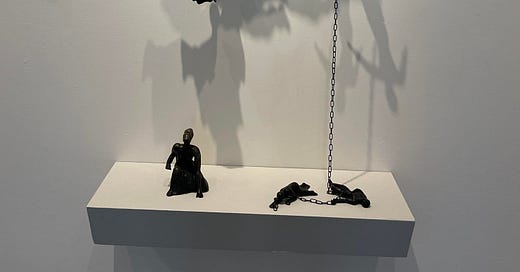

Capsize by Kyle Salandy, 2022

8.31.22 I was flying back to New Orleans Monday, fully aware as anyone who’s lived there what day it was. It was the sorrow twin anniversary of hurricanes Katrina (2005) and Ida (2021) and the painful resurfacing and celebration of those lost and displaced in the tragic storms. By now, August 29th is an annual reckoning, a yardstick used by communities and politicians and survivors and outsiders to measure how far the city and its brave, battered populace have come in rebuilding the broken neighborhoods and homes, how well shored-up levees have held up, and how much of the historic, ebullient spirit of New Orleans has returned to its tired people.

In truth, anyone who spends more than a few minutes in the city and across Louisiana knows that both Katrina and Ida are never far from memory. They serve a bookend of what was before and what is now, what should have happened then and didn’t happen to help its most vulnerable residents. Every year, pundits debate what lessons were learned, and what is being ignored at a high future cost to the city. Anniversary stories flood the headlines, and this year is no exception. I read about two new film projects I plan to watch. One is titled Katrina Babies and focuses on what’s happened to the children who survived Katrina. It’s been made by a local resident who asks all the angry and hard questions that should be asked by and for the residents of the 9th ward and other parts of the city that were historically neglected, and flooded badly during Katrina, and led to physical and cultural erasure of their communities.

The other is a scripted series coming out on Apple TV+, Five Days at Memorial, based on a New York Times Katrina story by a health journalist I know, Sherri Fink. She reviewed my 1994 global AIDS book, Moving Mountains, and I always read her when I see a story. She has a gift for narrative storytelling. She won a Pulitzer for the tragic story of how 45 patients at Memorial Medical Center died during Katrina, leaving a trail of accusations of criminal negligence and lawsuits in its wake, and much official handwringing. I won’t say more but urge you to watch the series.

One of the producers is John Ridley, also an NPR commentator who won an Oscar for his screenplay of 12 Years A Slave, the 2013 film. I was thinking about the series because I was on my way to Ochsner hospital on Monday afternoon. My car was at the mechanic’s shop, so I called an expensive Uber. The driver asked me to clarify which Ochsner I was going to, as there are several campuses. I said, the new one, on Jefferson, not the one on Napoleon, and he nodded. It was clear he knew what I was referring to, which was the former Memorial Medical Center hit-hard by Katrina, where those 45 people died. Everyone who’s a local knows this tragic story too well. I added, were you here? And he nodded.

Today, the hospital is called Ochsner Baptist; it was bought, rehabbed and renamed by the Ochsner health systems. It’s a first-rate facility that cares for the Saints football team. Like much of the physical architecture of the city, there’s not much outward trace of the tragedy when you drive by, but everyone knows what occurred there.

I’m an irrepressible journalist, always curious about people, and I asked the driver about his life, about that time. He’s almost 40, with family from Honduras, and his people, as he referred to his family, settled in La Place, in St. John the Baptist Parish. His mother has a house there. It’s about a 40-minute drive from Nola, a small town on the edge of Lake Pontchartrain, famous for andouille, a smoked sausage that originated in France. It’s served stuffed with fire-hot peppers and slow cooked for hours across Louisiana.

In 2005, La Place became a refuge for some of the Katrina survivors; it suffered relatively little damage compared to Nola. But the sky turned pitch black as Ida crossed the lake last year and pummeled La Place. My driver told me his mother and her friends got out in time, but her home was leveled. She got lucky—arguably—in that her insurance covered the rebuilding completely. Across the state, so many people remain in homes badly in need of repair.

After Katrina, several home insurers went bust, but were lured back to Louisiana by government officials who offered them help against future losses. IDA was a fresh blow to the industry and now, the pattern has been repeated. In January, I learned my Nola house insurer had gone bust and I scrambled to find another. Then in July, that insurer claimed bankruptcy. There’s only one insurance company, Louisiana Citizens, willing to insure houses with renters.

Meanwhile, during Covid, the city put a cap on evictions of renters; many had lost jobs. But that cap ended, and evictions have resumed of people who haven’t found new work or can’t afford the higher rents of the After Katrina-After Ida world. Housing and homelessness, coupled with Covid, are among the enduring aftershocks of the storms. New Orleans rebuilt its levees and held back the waters during Ida, but the wind caused a huge destruction of the power grid. The aftermath was a fresh portrait of disaster, and once again, the already vulnerable are hardest-hit.

I asked the driver about the rebuilding effort in La Place, the lessons of both hurricanes. He shook his head, dubious. La Place still lacks a levee, he said. His mother rebuilt her house exactly as it was, leaving it vulnerable to a future major storm. When I asked why she didn’t build it up higher, on pillars, like many have, he shrugged, as if the mysteries of his mother were impossible to penetrate. I assumed it might be for a basic reason, one limiting the rebuilding dreams of a lot of people: she didn’t have the money. Or maybe she can’t get insurance now. Or a loan. Maybe she rebuilt the same house because that’s all she could do and did so knowing full well she could suffer another major tragedy. That’s a common thread of life in a post-disaster world.

That said, life in La Place had largely regained its rhythms, he told me. It took a while, especially with Covid. But it’s all picking up. He normally drives from there to New Orleans to make money, but just this week, the demand for Uber drivers in his hometown is up. He’s hoping to stick closer to home. He has friends there and enjoys his life there. His mother lives on a quiet street, but it’s nice. There’s not much to do in La Place, but that’s okay. As he put it, and I’m paraphrasing, no storm is going to drive me or my momma away. It’s home.

I’m a Salt River Roarer! (Jordan Hess, 2022). Found objects from the ol’ Mississippi with missing sections replaced with steel armature and natural-colored epoxy sculpting resin displayed on custom pedestals. (On exhibit at the Ogden museum now.)

Ida was my first real experience of the famous mutual aid that people talked about as a high point of the post-Katrina period. The first afternoon I was back, on day three after Ida, still without basic services, my mensch neighbor stopped by to give me a spiffy generator; he’d bought a bigger one. I spent the week sleeping outside on my screened-in porch, glamping. I was lucky, compared to many, who sat in dark, molding houses. I’d make coffee with the generator and hand it over the fence to Berin, a neighbor and transplant from Portugal. He and his girlfriend, a Tulane grad, had signed up to help distribute food in a hard-hit area. I joined my neighbors to talk about what we could do to help the elderly and vulnerable in our St. Roch area. I drove my car to get bags of free ice and donate them to a pop-up store one neighbor made from their downstairs room for everyone to contribute. The Music Street Signal conversation we had was a constant buzz of reports on who needed what, and where to volunteer. This, I saw, was the true spirit and strength of New Orleans. Katrina had stiffened the backbone of storm veterans. They hopped up on broken roofs and tied down blue tarps. It was a constant movement of solidarity. Newcomers did their best to catch up. Everybody cooked for everybody. It was organic.

A year later, many of them have participated in myriad mutual aid groups that deepened their activity during Covid, focusing on the food workers and artists and musicians, and hospital workers and everyone else heavily impacted by the pandemic. That solidarity continues to drive the city forward. Amid the anniversaries, one can count the many, many community groups who’ve succeeded in pushing back against disaster, in seeding growth, and investing in cities across Louisiana for the current and next generations of youth.

Hell (Jimmy Nicholson, 1954—), 1979.

The other major ongoing response is a huge cultural outpouring of creativity and reflection about every aspect of the city and the storms and history of New Orleans going back to antebellum times. The storms have brought a sharp focus on climate change, and the imperiled bayous and Louisiana coastline. All of this has become an urgent subject of art and film and performance and theater and multimedia storytelling.

Today I stopped by the Ogden, which is an amazing museum, devoted to art from the South. When I moved to the city in 2020, seeing more art, particularly by Black and Brown artists, was a priority for me. The Ogden has been an incredible place to do that. I caught the last week of the annual Louisiana Contemporary show of works by state artists. I also stopped by rooms with works I saw a year ago, and I loved them as before. The museum’s work consistently reflects how deeply the legacy of slavery and racial erasure is a critical theme for contemporary Southern artists. I think of this as redress, writ large, a public conversation that integrates painful chapters like the murders of George Floyd or Breonna Taylor, or the imperiled farming and fishing communities across the state.

One of the most powerful examples at the Ogden is a painting, titled Belizaire and the Frey Children. A larger painting of three white children and a Black child is accompanied by a smaller, later reproduction of the same painting—minus the Black boy, who is identified as slave. This intentional and racist erasure was discovered when the original work was restored, and the hidden boy came into view below a patina of old enamel. The cover up is stomach-turning, though not especially a surprise given the brutal history of European slavery and the whiteness of art history, too. As I stood looking at both works, I thought about the artist who did the later work, commissioned to cover up the slave. What had he (It must have been a he) thinking when he did this? It’s so disgusting. I began to wonder how many other European family portraits may involve hidden racist erasures.

Belizaire and the Frey Children, circa 1837, attributed to Jacques Guillaume Lucien Amans (1801-1888). Original, top; reproduction, bottom.

A lot of work at museums I’ve visited in New Orleans are similarly concerned with historic and cultural erasure. Often, the artists are filling in what’s been left out of the picture but it takes the form of celebration, and ceremony, and sacred practice, though it’s always a form of redress and social commentary. There’s an incredible outpouring of portraiture and narrative art coming from younger Black and Brown artists, so much terrific work. Much of it directly references the racial erasure of the art canon like the Frey children, as well as gender issues, such as Hecate, (below) by Susan Ireland, that references a famous painting by Manet, a white European man.

The explosion of Black Southern contemporary art is also a result of thoughtful, critical attention to emerging artists by Black and Brown curators and scholars, many of them young women, who are building new audiences for this work, bringing art to communities. They include Valerie Cassel Oliver, the juror for this year’s Louisiana Contemporary.

Below are a few pieces from today’s visit to the Ogden that spoke to me. My favorite piece in the Ogden is a gorgeous piece by Whitfeld Lovell, Kin IX (To Make Your False Heart True) (below). His photography is stunning. The composition with the canteen bottle is a sharp historic statement. I thought of so many things… Black soldiers who helped defeat the Confederacy, Black pickers in the cotton fields denied enough water, Black makers of cane alcohol who ran bootleg distilleries in the Prohibition South. The canteen made me think of the Civil War and WW2, too. More erasures. I’ll be curious to read what the artist has to say about the piece. It may be nothing about any of that.

Further below are some links to the stories that continue to surface memory and pain and history and legacy during this sad anniversary week.

Hecate, Susan Ireland, 2021.

Differences. Trenity Thomas, 2020.

Kin IX (To Make Your False Heart True). Whitfeld Lovell (1959-), 2008.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/11/arts/television/five-days-at-memorial-apple.html

When I publish my Katrina book, I would love to be featured here to talk about the storm and some of the untold story of Mississippi during Katrina.

a fascinating story about your Ida experience