Game, Set, Match

How tennis reshaped my life.

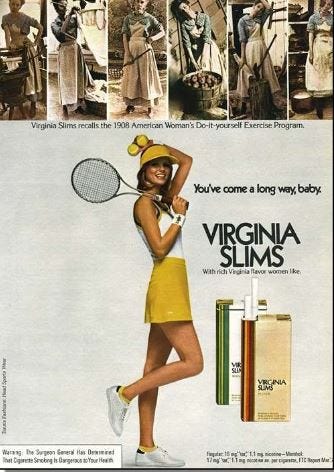

Virginia Slims women’s tennis tour advertisement, circa 1973.

9.10.22 I found myself back in Queens, NY, for the US Open women’s semi-finals on Thursday night. I sat in a high seat with a decent view of back-to-back matches between four outstanding players who would have beat me fast—the young me who thought I might one day play here, so long ago. It was hard to remember everyone I was with in the years after I left Rollins College and a serious tennis career for Barnard College and then Colombia journalism school. We’re talking 1970-1980s. I made the transition from competitive tennis—a sport that consumed my waking hours from junior high to sophomore year of college – for a new life and self in a big city far from Ormond Beach, Florida.

Tennis provided me with a focus for intense emotions and family crisis, letting me release furious energy for many years. It gave me a high school bestie, a fun college tennis posse of friends, a caring college tennis coach, my first lesbian girlfriend, and a sense of self that comes from repeated concentration and physical exertion and the necessity of shutting out the noise in one’s head. Tennis taught me to pre-see where I wanted a shot to go, to imagine my aces even if I couldn’t execute them on demand. I learned to let go, to stop overthinking, to trust my body. That practice and discipline later transferred to deadline journalism, and creative writing: Get out of your head, let go, trust, let it flow.

My best tennis came from that space. My worst came from failing, often enough, to play as well as I could. I was a bad loser, not with others, but with myself. For years, I broke rackets, lost my shit. I was highly competitive, and I cared about not losing maybe even more than winning at any cost. Looking back, I wonder if that’s what ultimately separated me from my friends who turned pro.

I began playing tennis at 13, when I went to a Catholic elementary school, St. Brendan’s, followed by Catholic high school. My teachers were nuns from the Bronx and young male teachers who tried not to flirt with their female students. My parents joined the tennis program at the nearby country club to prevent their children from being overly bored or becoming pot-smoking wastrels – this was the Allman Bros. 1970s -- and to prevent us girls – their two daughters – from getting distracted by long-haired surfer dudes who were, they were sure, trouble. Enter tennis. I played intensely for years. There was little time for partying, none for drugs. Tennis took up all the social bandwidth.

I was naturally butch, even as a young child, but not very aware of my sexuality or a sexual orientation. I thought of myself as normal and, early on, self-identified with boys. All my fantasies were about being the male heroes: I was a boy pirate, a global explorer, Tarzan--not Jane. I had an imaginary friend, Roy, named after Roy Rogers, the television cowboy I liked. We roamed the wild west of suburban Florida. I was a classic garcon manqué, or tomboy, one who chafed at wearing shirts as a child, and hated dresses, one who stole my older brother’s discarded smelly Converse high-tops to wear with my Catholic girl uniform. I got looks from others, but I didn’t care. I loved my grody high-tops.

Luckily, my mother was born in France, and being European, had a tolerant attitude toward my choices. She was an artist. Unfortunately, my father was very sensitive to what other people thought and was raised in a macho Haitian French culture. He was openly homophobic, a view that sharpened as I got older. Tennis not only helped shield me from my father’s intolerance but created a safe space for me to meet others like me at a time when being gay was completely unacceptable.

With tennis, no one challenged why I preferred to compete with boys instead of trying to date them. Tennis gave me my first job, stringing rackets, some money for myself. I had long Farrah Fawcett hair in high school and felt self-conscious about my Pop-Eye tennis biceps in my white Catholic school shirt and my muscular thighs that rubbed together. Tennis provided a cover for my disinterest in girly things.

My prized BJK racket.

When I look around the world now and see just how radically dress and fashion have changed, I’m amazed. Boys could never be allowed to wear an earring when I was younger: that spelled instant queer, and that spelled a pervert, and possible pedophile, someone to be shunned and feared. It was only in college, when I’d go home for a visit, that I paid more attention to the few unmarked bars in Daytona Beach with doors only open in the back where, I knew, men my father would despise were drinking inside. I didn’t know until later that high school male friends of mine might be in there. I didn’t even think about women going to gay bars. Gay people were just hated, and I had nothing to do with that public world. Until I did.

When I was sitting in the bleachers at the US Open, I thought about how my bestie in high school, Anne Mayer, would have so loved the match and crowd. We lost touch after college and reconnected through Facebook about three years ago. It’s like no time had passed, though so much happened to her and me. She remains a touchstone to my earlier tennis player self. We always had a blast, always laughing. I had other good friends in high school too, and we were not the most popular girls, but were freed, via sports, from the need to be so. Tennis let me get away from home, go on school trips. It let me spend social time with Black girls on the courts in my otherwise too-white Florida world.

Tennis gave me my first real love. My first girlfriend, Megan, also from Daytona, found me via the tennis courts. We went to different high schools, bonded at matches. Midway through college, that love triggered my move to NY, shifting everything.

‘The Battle of the Sexes’ — Billie Jean King vs. Bobby Riggs, 1973.

Photo credit: The Scottish Sun.

I had an earlier life hiccup in the spring of my senior year of high school. I’d gotten into Emory University in Atlanta as an early decision junior and didn’t apply anywhere else. A month before graduating, I toured Emory and hated it: it was freezing, and I’d worn shorts in late February. Frat boys were puking out of red cup beer keggers at the meet-and-greet socials. Cold Atlanta felt far away from my family. I quickly applied to Rollins College, in Winter Park, Fla, then the No. 2 college for tennis in the country, a launching pad for the pro circuit. Trinity was No. 1. I won a surprise tennis scholarship and, nearly every other weekend for two years, had to defend my 5 or 6 spot on the varsity team—and my scholarship.

Everyone assumed I might turn pro; I wasn’t sure. I didn’t want to play if I couldn’t be among the very best. I also played varsity basketball. That was fun, less hard. Several of my tennis buddies also played b-ball. We formed very tight friendships that have lasted all these years, even though we hardly see each other. I reconnected with one of them last year, Felicia Hutnick, nicknamed Flea. I was known as Gunner at Rollins, because I was a cocky frosh who gunned the ball. Flea now plays the senior golf circuit, after an earlier stint on the tennis pro tour. She took the route I didn’t and has had a great run.

Yvonne (Evonne) Goolagong, 1971. Photo credit: Nationaal Archief.

Together we went to see our amazing coach, Ginny Mack, who, at 97, is still active and lives alone in Melbourne, Florida, and likes to fish. On away games, we’d knock on her motel door to find a bathtub full of beer on ice. That wouldn’t happen in today’s tennis world. It was a different time. Ms. Mack was a fantastic, understanding coach, and always supported us. I have no idea if she knew I was struggling with my commitment to tennis, which started in my freshman year, or my sexuality, or my sadness about hard things at home. They were all connected. Two years ago, Rollins held a big celebration to honor her extraordinary career.

I started to come out after my sophomore year, when Megan seduced me on a trip to Europe. We were very close friends then. I’ll always feel badly for her; I was so deeply Catholic girl-closeted, so certain of my father’s complete rejection. That happened with him. My eventual coming out broke our relationship; we were never close again, not like before. I was even kicked out of the family will for a while. But everything else started to fall into place—except my tennis game. I fell in love.

I transferred to Barnard College, following Megan there, and quickly discovered the Big Apple. Barnard had a weak women’s team then, and for a few short weeks, I hit balls with the Columbia men’s team. But the guys didn’t want me there, and I felt like even more of a closet case. Instead, I soon discovered Greenwich Village, and Barnard lesbians, and Patti Smith and the 80s punk world of the East Village and the UK. The Clash, the Slits. I discovered writing and kept a journal. Tennis fell away.

I stopped competing by the time I graduated in 1979. I was burnt out. It took me a while before I could enjoy the game again. Back in Florida visiting my family, I’d play late at night, listening to southern rock over the court speakers. I’d rally with a friend, enjoying the arc of a forehand, or closing my eyes when trying to serve, getting into the old Zen flow of pure tennis.

The GOAT, legendary Serena Williams.

In the end, the closest I came to turning pro was the Virginia Slims Qualifying matches, the precursor to today’s Women’s Tennis Association. My college best was around number 22 nationally. Not shabby, but far from the extraordinary success of women like Jeanne and Chris Evert. By then, the Williams sisters, Serena and Venus, were rising stars. All of my Rollins varsity teammates turned pro, I later learned. At the US Open, we hung out in a Queens restaurant with newcomer Martina Navratilova, who had a heavy Czech accent then, and an intimidating serve. We joshed with Rosie Casals, a doubles superstar with Bille Jean King. Ilie Nastase was around, and Bjorn Borg. I was a fangirl of Yvonne Goolagong, her mentoring of other Aussie Aboriginal players. I glimpsed the life I’d dreamed about. Being pro was hard; women made so much less than the male players. The sexism was still so entrenched; so was the whiteness. I had no regrets, and so many great memories.

Looking down from the stadium seats on Thursday night, watching a younger generation of players warm up, it all came back. Who I was, what I became, what didn’t happen, what did. What’s changed so, so much. I started playing with a wooden Billie Jean King racket at age 13 and had to wear skirts to compete. Homophobia was rife. Martina later came out, breaking that barrier, and, later, Billie Jean King and others. Renee Richards, who coached Martina, put a face on transgender identity, and the struggle of trans athletes.

Fast forward to the semi-finals. I was hoping I’d be watching amazing Serena play but she lost in the third round and has retired, the GOAT—Greatest Of All Time. Her mega-talented older sister Venus is still playing and is a phenomenal doubles player, too. Before them, Althea Gibson was the great Black woman tennis pioneer. They and other women of color have opened the door for rising talents like Coco Gauff, and Ons Jabeur, who is Tunisian. I cheered her on Thursday as she won her match, becoming the first African and Arab woman to reach the semi-finals, a new milestone. She broke that barrier at Wimbledon earlier this year. Via text, Megan and I traded updates on the match. She’s back living in Florida, a mad sports fan. Tennis and body surfing are her jam. We’re family, the lesbian way.

From my view in the stands, tennis just keeps getting better.

Ons Jabeur, a global symbol of hope and strength for millions of Arab and African women.

Photo credit: Africa 24.

Gunner (l), Coach Mack, Flea (r), Spring 2022.

Photo credit: Juno Rosenhaus.

Thanks to all commenting here and on FB. I've fixed a few typos, added the critical bit about falling in love thanks for Cupid Tennis. Appreciate all the comments, and your own reflections from that time if you are, like me, a former serious college player. When I was watching the terrific TV series, A League of Their Own, it all felt so familiar, especially the closet. Even without turning pro, that's how life and sisterhood and secret romances and the tacit racism and sexism of the 70s felt like in my tennis world. There was a lot to love, and a lot to hate, and fight. The pioneers of my time -- Martina, Billie Jean and Rosie, later Serena and Venus, Yvonne Goolagong--and importantly, Renee Richards -- were subjected to far more discrimination than any story can tell. I watched King Richard just before the semis, and thought: yes, yes, yes, that is how it felt and was, in central Florida, where we were dreaming tennis.

Wonderful descriptions and full-circle memories; the road not taken still leads somewhere .