New Series Launch - A Flaneur with a Beat.

A Spotlight Conversation with writer Ann Rower (Part 1 of 2).

11.4.22

Welcome to my first big Spotlight, a weekly series of intimate and in-depth conversations and reflections about lifelong activism and creative work with queer and gender rights pioneers. I’ve started with my expanded personal NYC 90s world of activists and artists and globally. I’ve invited friends and colleagues to share ideas for exciting voices they’d like to hear from, who sets the bar for them. I’m hoping this series inspires you and gives you fresh ideas for how to keep fighting your good fight and making your important work, too. So — welcome to the big conversation. This party is starting! — Anne-christine

First up is Ann Rower, a writer and longtime New Yorker who I’d been out of touch with while living on the West Coast, though we are friends from the heady 90s days in the East Village. I’ve broken up our conversation into two parts, because we do go deep and it’s compelling.

The writer Ann Rower. Photo:

Part One: Catching Up

Over a year ago, in the thick of Covid, I was still in New Orleans, but slipping up more often to New York City to reconnect with old friends and activist colleagues, many from our heyday wild lives in the 80s and 90s. I’d missed Ann Rower, an old dear friend and writer who’d moved from Avenue C in the East Village to an Upper West Side brownstone with her lover Val Clark. We hadn’t seen each other since Pride 2017, where she joined an event that I organized at the LGBTQ Center for writers lost to AIDS. We finally caught up last week and have been talking since. Val had shockingly died two years ago, I learned right away. Covid quarantine had been really tough. Ann rarely ventured downtown anymore; her bad legs made walking difficult. On the plus side, she was finally writing again after years of feeling blocked. I’d clearly missed some major chapters of her life. Jeez, I thought, you blink and so much can change.

Ann and I met and bonded in the early 90s, living near each other on 7th street and Avenue C. We were both working on books and also, not working on our books. The not working – the struggle to nail down our big books – became a reason to meet for a quick late afternoon whiskey around Thompkins Square Park. We’d commiserate -- and gossip. I was working on my first novel, Under the Bone (FSG), based on my 80s political reporting in Haiti. She was struggling with Lee and Elaine, a fantasy story in which she reimagined the famous Abstract Expressionist writers Lee Krasner and Elaine de Kooning hooking up for a lesbian romance, grooving on each other more their more famous male lovers, the 50s hot art bad boys Jackson Pollack and Willem de Kooning. Ann related to the 1950s Mad Men narrative of talented women who dutifully marry and stuff their dreams and desire. That was the early part of her own story. She only fully came out as a lesbian and writer in her 40s, and, to this day, she feels she’s making up for those lost years.

I don’t know how much time I’ll have left so all I want to do is write, Ann tells me, when we sit down in her kitchen to catch up. After Val’s death, something shifted, and I suddenly began remembering all these things. All these stories began pouring out of me. I can’t write fast enough.

Ann, who is over 70 – let’s leave it at that – is the author of three books and a contributor to others. They include If You’re A Girl with Semiotext(e)’s Native Agents imprint, founded by writer Chris Kraus, and Armed Response and Lee and Elaine, published by High Risk Books, and edited by Amy Scholder. I knew Ann’s name by reputation before we met. She was part of Kraus and Scholder’s LA and Loisada crowd -- cool older women writers and poets, straight and bi-- including Lynne Tillman, Cookie Mueller, Barbarg Barg, Diane Torr and Eileen Myles.

That crowd had lived a bit wildly for decades, fucking and getting fucked up by the bad boys –and some girls. They wrote about it in edgy super personal, confessional stories and poems, many of them first published by Kraus via Native Agents. She launched her imprint as a feminist riposte and counterpoint to Foreign Agents, a Semiotext(e) imprint edited by her then-more-famous husband Sylvere Lotringer. Kraus is the author of several books, including I Love Dick, a hybrid story of thwarted female desire and obsession. I Love Dick was later revamped as a television series, helmed by Joey Soloway, elevating Chris’s indie celebrity. In the show, Kevin Bacon plays the sexy famous male art star cowboy guy with the outsize ego, while hottie Kathryn Hahn plays Kraus, the jilted, desiring lover. Soloway’s then-lover Eileen Myles had a big cameo character plot line; the talented lesbian actor Cherry Jones played Myles with her own butch cowboy swagger.

Kraus was the first editor to look seriously at Ann’s work, and today, the two of them are collaborating on an expanded version of If You’re A Girl, due out in 2023. Ann had just finished the last of the stories when I we met -- or so she thought. The next day, she told me that our conversation had spurred her memory, and she was writing some new stuff that may get added to the new book. It will include a bunch of early stories that Ann had actually forgotten about until fate – good fate in this case --intervened.

Can you believe I’m living here? Ann says. I can’t, actually. Her building has an elevator and a doorman. The apartment is large, the entry hallway and bedroom lined with Val and Ann’s books. It’s very different from the cozy ground floor Avenue C apartment she lived in for years, often sharing it with one lover or another. In the 90s, she was dating Heather Lewis, a talented writer and lesbian who tragically killed herself when they were together. The event unmoored Ann for years; she tried to write about it but it’s been too hard. After Heather’s death, she met Val, a close friend of Heather’s. Their grief bonded them and they fell in love. Then another tragedy hit: Super Storm Sandy. Ann’s apartment flooded; her home was unlivable for months. The couple took refuge uptown in the apartment owned by Val’s family. They realized it was a better fit. By then, both of them were having real health issues, including lifelong diabetes for Val. For a while, it was good—a reprieve. Then Val’s heart stopped.

Can you believe my bad luck? Ann asks me. First Heather, then Val. I still can’t quite believe it myself. She’d barely gotten through years of depression after Lewis’s suicide. She and Val were actually having a fight that morning, she recalls, and Val locked herself in the bathroom. She heard Val calling but it was too late. They still don’t know the real cause of death. Val had so many health problems, including the diabetes, says Ann. Still, it was a total shock. Ann decided to stay living there, surrounded with Val’s book and all their memories.

You can just never know where life will take you, she muses, still unable to process it somewhere. I miss Val and I’m so grateful to have this place to live and to work. She’s gotten help and has a roommate, and to her surprise, she’s writing again, furiously. It’s the only good thing that’s come out of all this, if you can dare to even call anything good, she tells me. The shock of Val’s death dislodged something. Memories, whole swaths of life. She has her voice back. I just wrote a book in three months. It seems like a miracle. I have no idea if it will last, but I’m just so, so happy about this.

Another miracle happened, too. After Val’s death, a friend who had stored some of Val’s things got in touch. Val had kept Ann’s first draft of If You’re A Girl and other unpublished stories. She’d forgotten most of it. She sat in her kitchen for hours, reading, amazed at rediscovering her earlier self so many years later. Even better, she liked what she was reading. I think the stories are good, she adds. Good enough to be published, she felt. Screwing up her courage, she contacted Kraus, who read the old-new stories and agreed. All of that just opened things up, she adds.

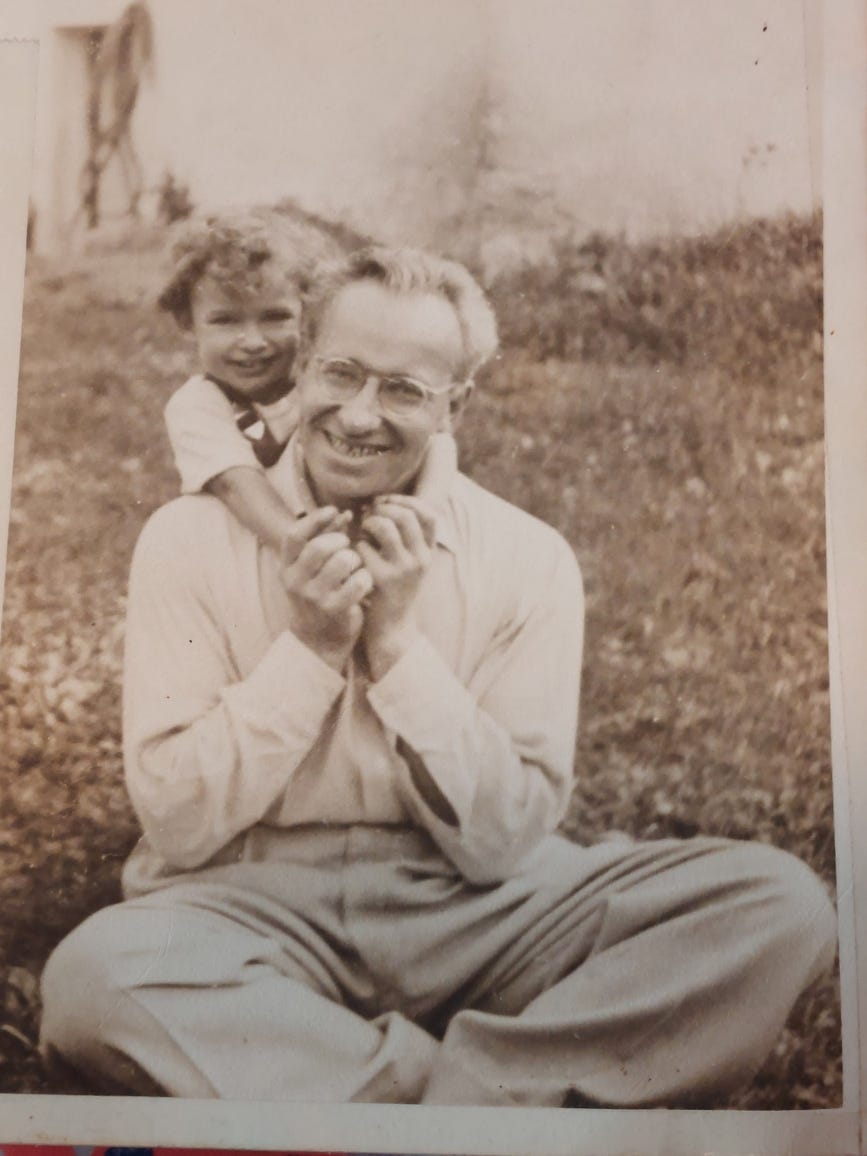

Ann with Dad: 'I learned to work hard from him.’ Photo: Ann Rower personal collection.

Ann is a Jersey girl, born in Newark. She grew up in the suburbs, an only child. Her father was a juvenile delinquent specialist and counselor; her mother was a children’s book librarian. She read a lot to Ann, seeding her early love of stories. She admired her father for his strong work ethic; he worked six days a week. She considers herself somewhat of a Red Diaper baby. My father was a communist at some point; he stopped when Stalin invaded Poland, she tells me. My parents then became sort of post-political. The family moved to Great Neck, Long Island, where, Ann says, they didn’t fit into the rich, snobbier scene.

As a child, she was quiet and bookish. I was quite solitary, but I had a lot of friends, she recalls. I went to a little progressive school in New Jersey. It was very good. I had a lovely joyous childhood. I was also the dutiful girl -- the good girl, she recalls, smirking at bit at the thought. I wanted to please my parents. I loved them very much, except that my mother turned out to be homophobic in my youth. That sort of changed everything.

Rower was 14 and going to an arts camp on Cape Cod. I fell in love with my friend named Margot Lewison. She was 14 and big and tall…. I think I had a consciousness of it, she says of her nascent lesbianism. I knew all these gay kids. So, it wasn’t scary or anything -- I was proud of it.

Her mother felt very differently. Like a classic coming-out scene in a 1950’s novel, Ann’s mother walked into her bedroom one day and found a cache of love letters from Margot. She left the desk drawer open with the letters exposed, so I knew she’d been into my drawers. I could tell by her face she was not happy. I got “the lecture” – Ann uses air quotes to emphasize it – you get from liberal parents. ‘Oh, but not my child….’

It scared me straight, she adds. From that moment, she repressed her desire for women, though, she admits, I didn’t stop seeing Margot until I was about 25. I snuck off in Greenwich Village….

That wasn’t her only secret. By high school, she was becoming a speed freak. My mother took me to a diet doctor and he gave us diet pills. She didn’t like them, so she gave me hers; I liked them. That began a lifelong on-off relationship with pills. I only took speed to write, she explains. I was always scribbling in my journals. I’d stay up all night. Writing, writing, writing. I wasn’t doing it to get high, she insists.

What was she writing about? She has no idea. I’d love to find those journals, she says. What stuck was her habit of writing loosely, organically, one thought leading to another, an act of free association. The tone is loose, casual, first person, confessional, a diary. Kraus and others have labeled her writer’s style digressive – like a series of digressions, though Gary Indiana, once described it as ‘championship chess moves disguised as digressions’. I think of her as a flaneur with words, one who’s happy to stroll along and check out the side streets. The idea pleases her.

I never start out thinking about what I want to write about, she says. She’s tried to do that, but it’s like wearing a poorly fitting suit. She once spent years trying to write a conventional biography of her larger-than-life uncle Leo and his Los Angeles circle. She had 1500 pages and no ending when a kind editor gave it to her straight. Let it go, that’s what he told me…you can’t write that way. She’s another kind of biographer, the one who sees married Elaine and Lee falling for each other, a fantasy she now views as a way to talk about her delayed coming out -- a revenge vehicle for the lost years. I just suppressed everything. My sexuality. I put it all away. It took her until the 90s to finally choose women.

1950’s dinner plate with diet pill ad.

Her first marriage was an act of contrition; she’d regain her mother’s love, her parent’s approval. I don’t really understand it to this day... it was the late 50s, early 60’s…you got married. He was really an idiot, she says of her first husband, shrugging her shoulders, still irritated at her bad choices. He was a poet, and very adventurous and handsome. But it was a somewhat passionless relationship. I was married three years to the day. My father took me down to El Paso and over to Juarez to get a Mexican divorce. I got some Mexican glassware and came home.

Things picked up in college, first at the University of Michigan, then grad school at Radcliffe. She later got a PhD in Literature from Columbia, in order to secure her first teaching job at Brooklyn College. She wasn’t an academic; she wanted to write. Instead, she taught books. After the first idiot husband, she married another man, then divorced him after three years. When I ask about him, she bats away the memory.

While at Radcliffe, an event occurred that she says completely reoriented the direction of my life. A friend introduced her to Timothy Leary, the guru of LSD, who was conducting psilocybin experiments with Harvard students. Ann and her husband were soon hosting weekends in the Boston ‘burbs where she and other students would trip their heads off as Leary took notes. I can’t say it was a bad experience for me, she says immediately. It just completely changed everything.

END OF PART ONE. PART TWO CONTINUES ANN’S STORY ON SUBSTACK.

This Spotlight Conversation with Ann Rower (Parts 1 of 2) is copyright material of author Anne-christine d’Adesky. No part of this story shall be republished without the author’s prior permission. © Anne-christine d’Adesky, November 2022. All Rights Reserved. For information, email: talktothefuture@gmail.com.

Very interesting woman. I want to read the Elaine and Lee book.