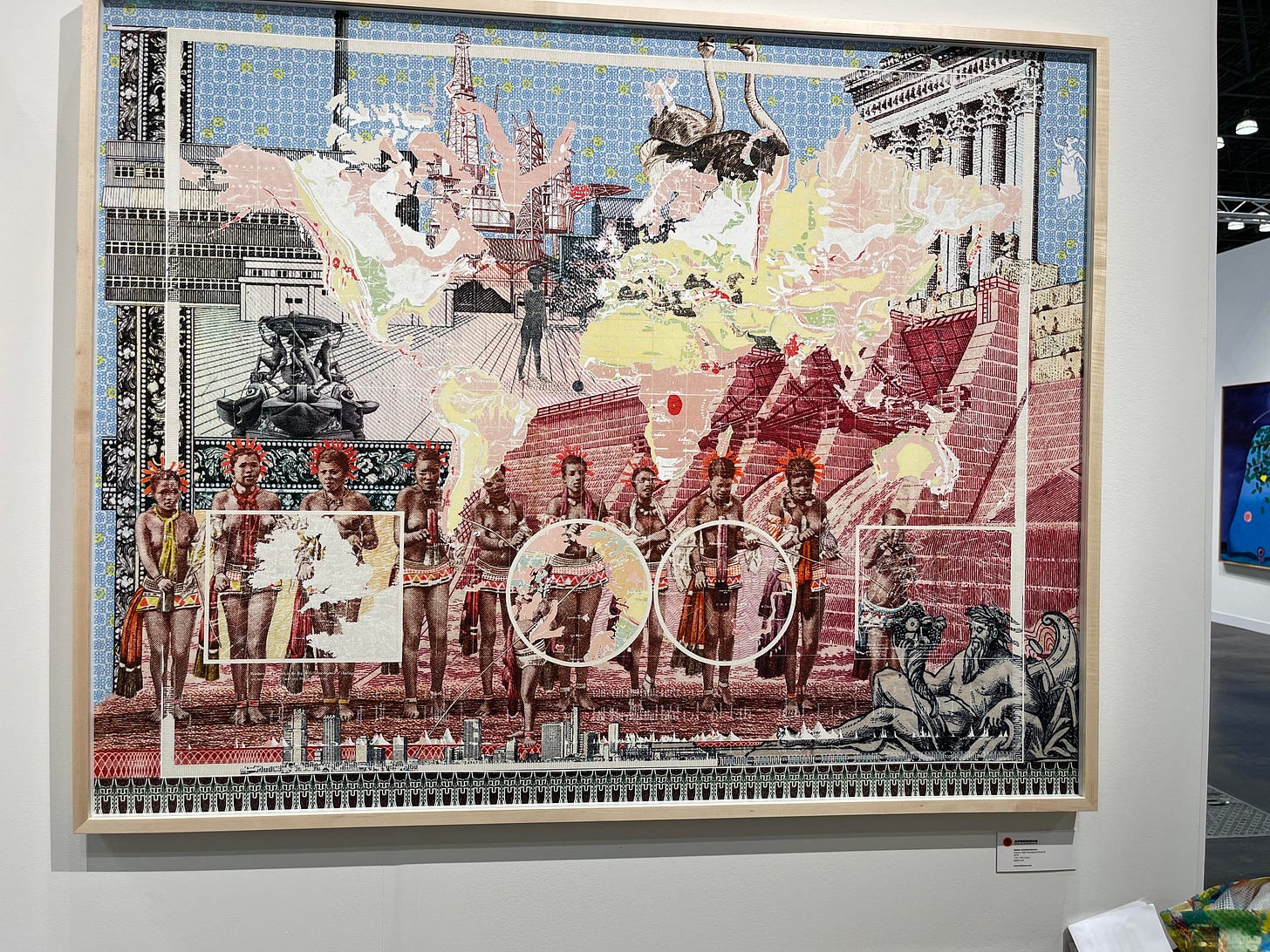

Detail of a tapestry map by Thania Petersen.

I was lucky to secure a pass to this year’s Armory Show, an annual smorgasbord of art that was held at the Javits Center in Manhattan. Art fairs like this feel like Disneyland, with too much to see, and different kinds of visual work thrown together, including more commercial art and finer art in different media. It also feels like commerce, which it is. The show is about money, and selling art, and a chance for dealers to showcase collections and hobnob with each other and the public. Tickets are expensive, and there’s a VIP section, so the event feels fancy and designed to make you feel like you’ve landed in an exclusive spot.

I’ve been before, and I like to go, but not because it’s exclusive. I’m a small d democrat; I like art to be free and inviting to a large public. I was given a free ticket by an art industry friend; otherwise, it’s so costly and it reminds me that the business of art is much like fashion, meaning taste is subjective and subject to hype and celebrity culture. Whatever generates a buzz or a little controversy spells cash, or might. There’s a lot of not-so-special art out there seeking its 15-minutes-of-fame.

Industry people go the Armory because they like to see what’s generating the buzz, and to follow certain artists, and because they love art, too. Art is a huge business, and viewed as a smart long-term financial strategy, given these precarious economic times, with plummeting Bitcoin stocks. I’d buy so much art if I could, not to invest, but just for the great joy I feel looking at paintings and other visual images. Art also engages me because it reflects shifting social concerns and history. It mirrors the changing world.

Thania Petersen

This year’s Armory was a dip into personal geographies, those of artists who are reworking images and ideas from the past, including the colonial past, to reveal new truths and reframe painful chapters of history. Then there’s the sheer dazzling pleasure to be had from their ability to render people and subjects in paint and charcoal on canvas or vellum or other media—the pleasure of line and stroke, of tactile surface, of bold and shadowed gaze. Good art speaks for itself: you’re drawn to it, you study it, you can’t turn easily away, and you marvel at how what can appear simple or effortless reflects a mastery of composition and perspective. I swoon before art I like; I just can’t get enough of it. I think, oh this is just fantastic. Look at that, look at that. Gorgeous, so smart. I like what they are saying. I’ll share some of the work I really enjoyed here.

I know what I like. I was on the lookout for art by contemporary African painters, particularly portraits, which are my jam. I’ve been enjoying and educating myself about the works of emerging and established African painters as well as older artists going back to the 1950’s. I know it’s making a grand statement to say that so much of this work concerns itself with redress and history and empire, but that’s not overstating it. Many African artists are reworking what’s passed for the all-too-white canon of art history, often reframing classic images to present a new map of their personal geography, as I think of it. It’s reclamation, and it’s often done with brash humor. Many are multimedia artists, mixing images and drawing from the popular culture of their childhood or past, including cartoons and images from African cinema and magazines. Many diasporic and African-American and other artists of color are engaged in similar visual acts of historic and cultural reclamation.

when the cry takes root (Ebony G. Patterson, 2020)

Near the show entrance, I came upon Ebony Patterson’s big floor peacock sculpture spread across the floor, a colorful, glittery tapestry of bead macrame, feathers, gilded conch shells and plastic ornament entitled …when the cry takes root. She’s from Jamaica, and her sculpture makes reference to 19th-century slavery. She did research at Hope Botanical Gardens in her native Kingston, a former British plantation. I’ll quote from the Armory panel describing this piece, in which she ‘… considers gardens as spaces of both beauty and burial, serving as postcolonial symbols of pasts that are never completely buried nor completely visible….’

I was also struck by the similarities in the work of two African artists, also preoccupied with the subject of colonial geography. South Africa’s Thania Peterson hails from Cape Town, has a global following, is collected by major museums. A South African of Indian descent, she presented several handwoven tapestry-maps of Africa that presented new narratives of colonization and migration, replete with allegorical imagery. One sees the white sails of ships carrying European Crusaders and, in the foreground, a large crocodile about to swallow one of the white knights on horseback. Towering above the hills is an African queen, an aura of gold and jewels framing her face like Ethiopian religious figures. Is she an African Virgin Mary or one of the many African queens of Africa who resisted the Crusaders? In another, the figure is an Asian female and here, a Black female fighter is riding the horse and Black figures have taken over sailing the enemy’s boats. Peterson traces her own roots back to the 18th-century Indonesian prince Tuan Guru. She is interrogating her personal history, too.

There’s a lot of humor in her gorgeous, layered landscape, including smiling mouths with small white feet that draw from contemporary cartoon and phantasmagorical creatures drawn from a medieval bestiary. What stands out is her deft, precise needlework, and the brilliance of tapestry she achieves. Her female figures reminded me of reverse glass painting portraits of Indian women I saw in the street markets of Bombay and of Indian miniatures, and the rich hand-embroidered wedding coats for men. The historic and cultural references were both overt and subtle, the overall effect rather spectacular.

At a stone’s throw from this work was an exhibit of equally busy territoires, as I thought of it, by Malala Andrialavidrazana, who was born in Madagascar and moved to Paris when she was 12. Two of her big 2021 collage atlases of 19th century pillage are entitled Figures 1898, and Les Grandes Communications. She’s a mixed-media artist, drawing connections between the brutal reigns of rulers like the brutal slaver King Leopold in the Congo to current events like police brutality and murders that sparked Black Lives Matter. Like Peterson, she makes the connections for us, while layering in images and ideas that make us consider other historic linkages, too.

Malala Adrialavidrazana

I really like her use of white space, in the form of what looks like a worn-out surface in the shape of Africa that is superimposed over traditional bare-breasted ‘native’ images of African women, a colonial and post-colonial staple. All of it forces a viewer to consider how entrenched the male, white, European-rooted gaze is upon the enslaved subject of African women, and the economic currency of Black female bodies, naked or half-naked, and as part of the romance of 19th-century empire and its sexual and geographic conquest of Africa. Like Patterson, she layers her compositions with plant leaves and bead shapes—the original currency of African traders.

Malala Adrialavidrazana

I wish the curators had put their exhibits side by side, or facing each other, to further our consideration of the connections to be made, past to present, old to new empire.

That leaves portraits, of which there were so many I thought were terrific. I won’t go into detail about them, except to say that what came to mind, not for the first time, was how some contemporary African painters borrow liberally from the local environments around them including patterns and fabric and signage and the activity in local markets. The position of some portrait subjects – formal and still, rigid-backed, serious – remind me of the celebrated studio portraits of great African photographers like Seydou Keita. Many contemporary African painters like to reproduce the patterns of African wax print, a colorful pattern fabric derived from colonial Dutch wax prints. That’s where you find more subtle, but clear, references to colonization and independence, and again, redress—a contemporary reclaiming and celebration of African popular culture, dress, custom and traditions.

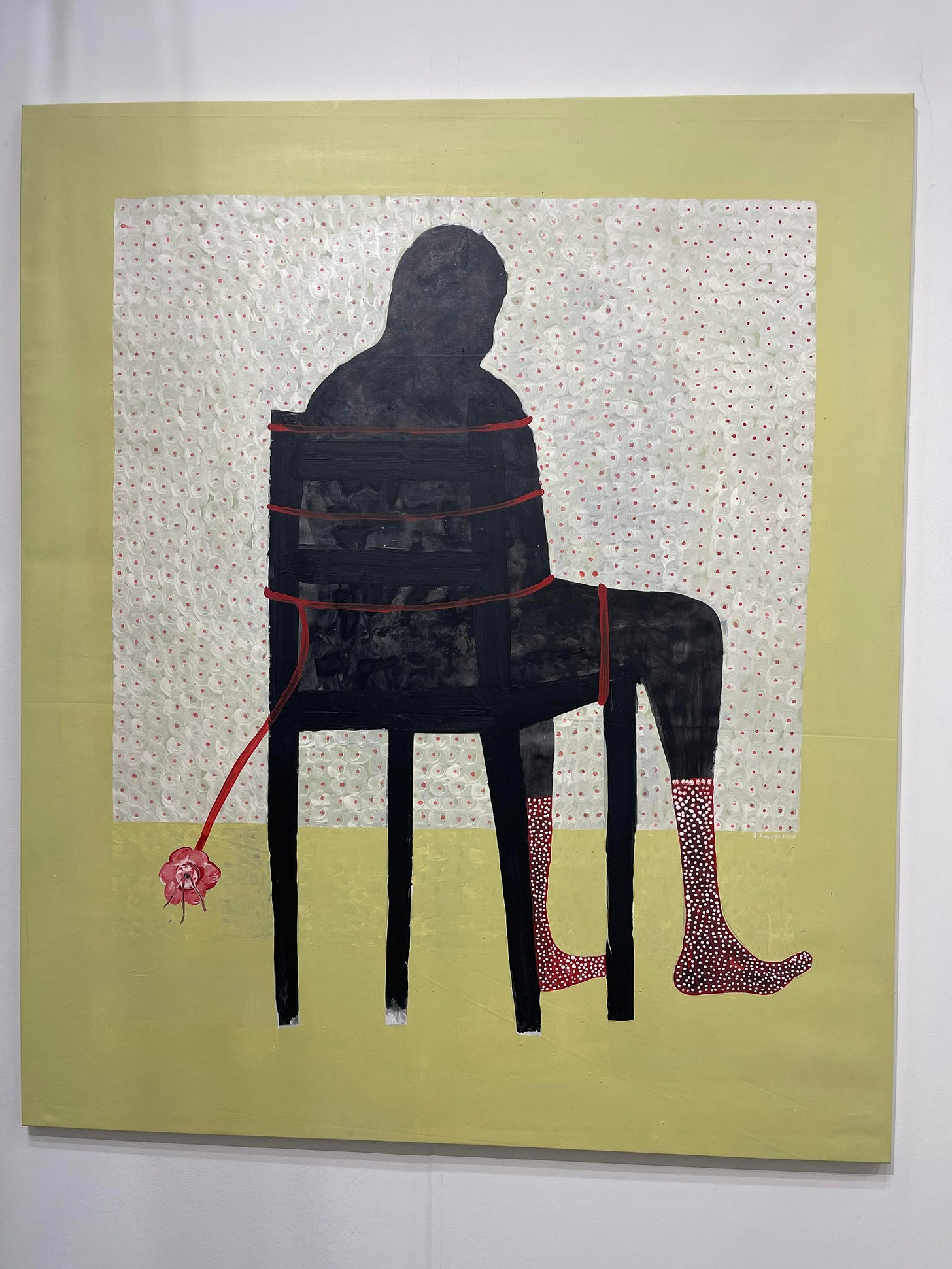

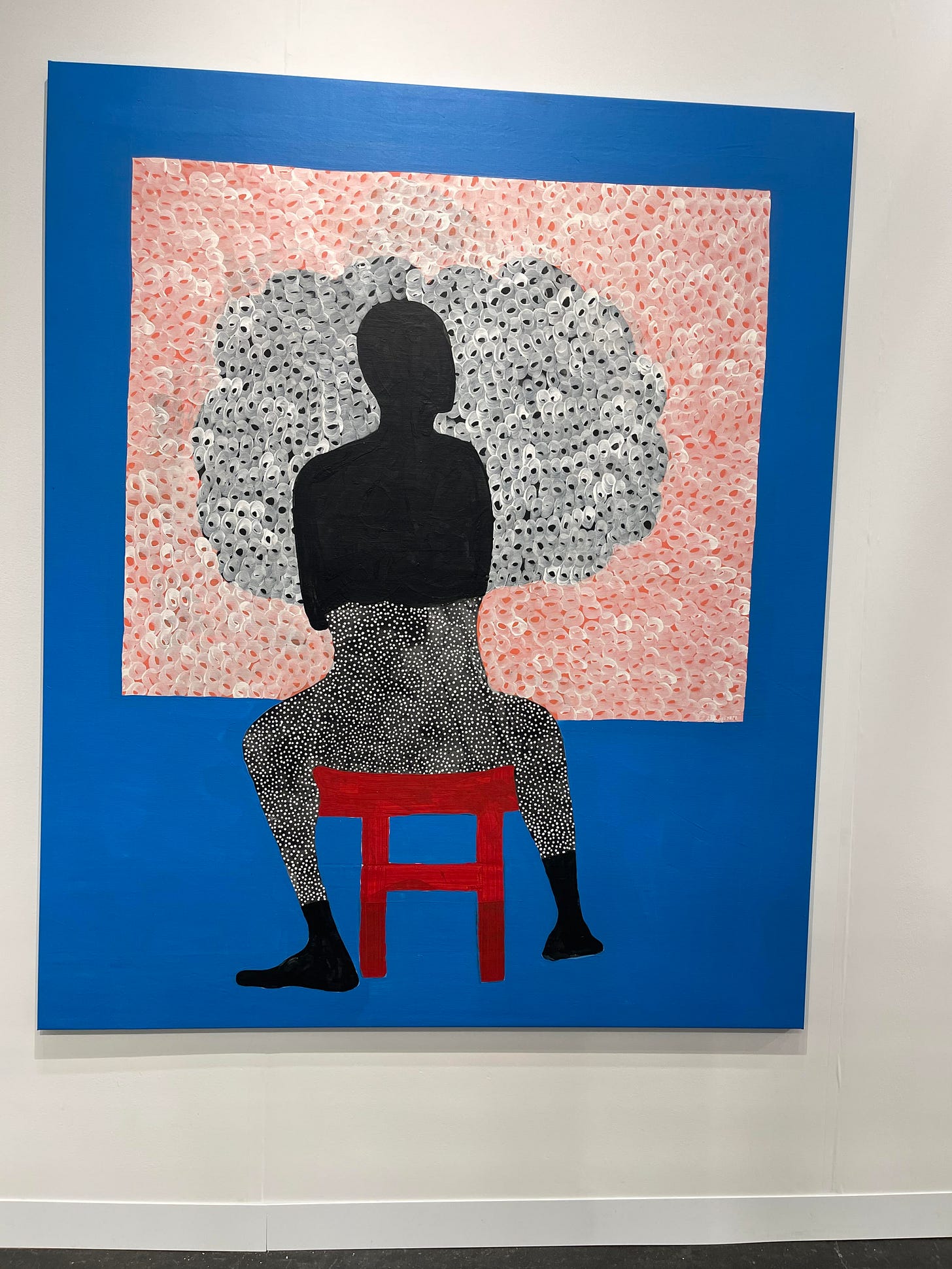

I really loved all the portraits by Amadou Sanogo, whose use of block color backgrounds and black and white space are very contemporary and reference traditional African sculpture and masks. Look at the painting of the man tied down by a red line linked to a red rose. The visual reference to slavery and possible torture is overt, and that leads to a surprise. Where one expects a heavy black iron ball-and-chain sprouts a flower. The man’s socks are red with white spots. There are sexual references too, to light bondage.

Amadou Sanogo

In this painting and the others, his seated figures have their back to the viewer, a break from traditional portraiture. They could be facing…what? A grey cloud in a red dawn sky? A painting? The more I looked at it, the more possibilities emerged. They are serious and they are fun.

Amadou Sanogo.

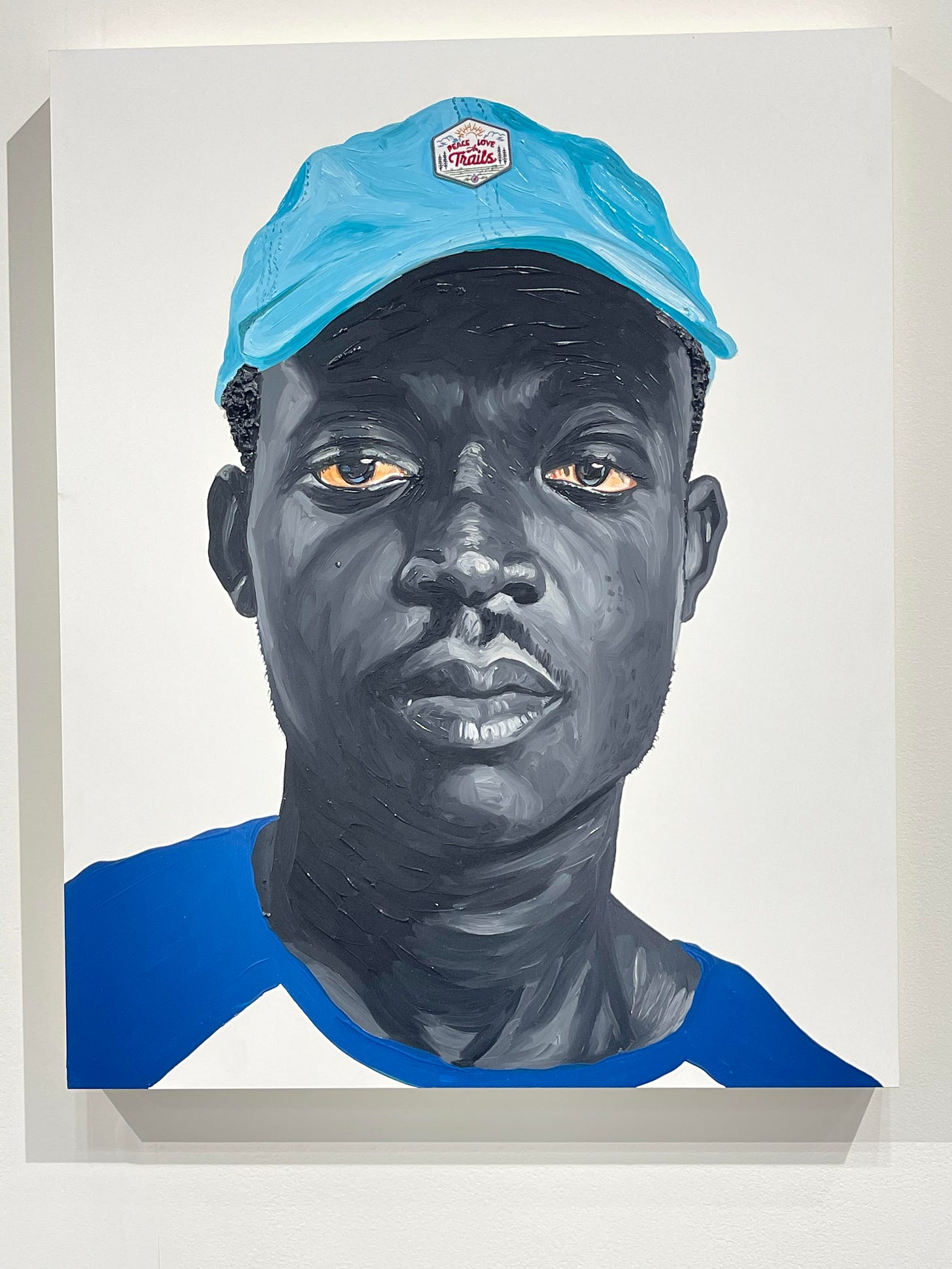

Another male artist from West Africa, Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe, hails from Ghana. I really like his portrait Out of the Blue (2022), made of oil and acrylic and applique on a panel, and two portraits by Nigeria’s Collins Obijiaku’s, Tofu and Balogun (2022) and Daniel (2022).

Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe

Obijiaku is a self-taught artist who discovered art on the internet, and never went to art school. I like the way he swirls his brush to create facial features with a creamy brown palette, and the unfinished brushstrokes of a purple shirt. Like many contemporary artists, he’s not after a smooth finished portrait—on the contrary. He wants you to see how he’s made his pictures, with his hands. They feel tactile, with suggestive dimension. These African men gaze directly at the camera, strong, self-possessed.

Collins Obijiaku

I always look up the artists and the work after I’ve seen a show, further educate myself. Then I look at all the work again and feel more discovery. Quaicoe is from Accra, and ended up moving to Portland, OR in 2017. He’s buddies with two other rising African artists, Amoako Boafo and Kwesi Botchway. I’ve seen a lot of Boafo’s work in major shows in the US in recent years, including in LA. His signature brushwork is unmistakable. When I saw Boafo’s piece at the Armory (below), with its colonial reference, I thought: oh, look, he’s become more overtly political, too.

Victory Band Overcoat (Amoako Boafo)

In one article I read, Quaicoe talked about how his own Ghanian government doesn’t realize how big he and other African art stars have become, and the currency—the cultural and art market dollar power – they now have. He’s hoping that power can help develop the art scene in Ghana, which only had one art school as of last year. He and his famous art buddies were about to open the first exhibition of their work together in Accra’s Gallery 57, entitled, fittingly Homecoming, and subtitled, The Aesthetic of the Cool.

For his part, Obijiaku represents a wave of younger Black figurative painters whose compositions may reference earlier and European portraiture but whose eyes are fully on Africa in the present. When asked about his artistic ambitions, he said in 2020 that his goals were simple: I am documenting my time. He wants to show the beauty of the people around him and their lives. His personal geography, then. Set against the historic, racial erasure of Africa’s culture and history and artistic legacy, that’s also a definite act of reclamation.

(above) detail of a tapestry map by Thania Petersen

https://www.everard-read-capetown.co.za/artist/THANIA_PETERSEN/biography/

http://www.andrialavidrazana.com/biography

https://news.artnet.com/art-world/otis-kwame-kye-quaicoe-1953341

https://www.robertsprojectsla.com/artists/collins-obijiaku

Thanks for introducing me to all this fascinating work, Annie! I love love love it all! and love how you walk me through your thinking on it.