For Lynne, her brother, and her family.

8.28.22 Yesterday a friend I made during the pandemic texted to let me know her brother had died. He’d been sick with a cancer that had a very low rate of treatment success, and he’d waged an epic battle to live for two years. Her pandemic isolation, and that of her brother’s family – his wife and two younger boys – was compounded by the intense demands of quarantine. Every visit to him, at home or to doctors or hospitals, was fraught. The non-ill threatened the more vulnerable. My friend, who adores her brother, had to weigh the risk of seeing other people and balancing her life with friendship and support, with the risk of a further threat to his health. She huddled with her family. Everyone’s life fell into limbo.

I lived that limbo, many years back, when I was going into high school, and then coming out of college. My mother’s recurring cancer ended with a death, fast, but not fast enough to spare her incredible suffering, and only after years of limbo, another word for remission. Unlike my friend’s brother, my mother had a long stretch of good years in between the first shock and the final one. But I now know I can’t appreciate how complicated the days in between were for her, too, never knowing how long her get-out-of-jail card would last.

When my friend texted me yesterday, I felt a familiar feeling, one that I’d felt for almost two years after my mother died. A sharpness that extended grief and final loss can bring to your days. An emotional state that clarifies and flattens at the same time. I felt like I was looking through a looking glass back then, a thick pane, cutting me off from my past, and who I’d been before. I felt I couldn’t step back through, couldn’t recover what I’d had or been up to then.

I’d had to leave my life in New York, return to my family’s home in northern Florida, which felt like an emotional exile. It was an incredibly difficult and lonely time. I took care of my father and older sister, then very ill herself with schizophrenia, and my younger brother, and sometimes my French grandfather, all of us shattered and trying to see our way forward.

When I say flattening, it’s like the day sometimes felt like it had no dimension, like I was looking at everything outside of me like a movie set, without real buildings behind the storefronts, and I was a character moving through it. Yet everything felt freighted. I felt flat and so full of grief that I felt my eyes could leech colors from the trees. The grass was extra-green; the ocean off Daytona Beach extra murky brown-green. I knew fish and sharks lived there, but I couldn’t imagine how.

Yesterday, the text message pulled back the emotional page in a second. I was in the car, a blue MGB-GT, with the top down, and warm humid air was blowing around my face, and I hung my arm out the window and played a game with the breeze. It was just past dawn—earlier than most people got up—and I was driving with my newish limbo-land friend, Brooke. She was sad, too, and droll and sharp. She was one of the only people I clicked with during the nine months I lived back home. We could sit silently together. Earlier that spring, she’d walked off a roof party in New York. She’d been drinking. She fell two stories onto a car and broke both legs, all the way up to her hips. When I met her, she was already walking with a cane, and worried she would get addicted to the pain pills. Her dry black humor was razor-sharp. It was immediately clear she could see with the same flat x-ray vision of a broken heart as me. Hers was about losing her health, and also leaving New York. She was back living with her evangelist older parents, in a larger trailer. Her father liked to fish.

I was driving to Cassadaga in the fancy sports car my mother had always dreamed of having. She’d held off, always sacrificing her fun to assure the family’s economic future. She bought it when she was already sick. We all knew it was a buoy, to help her keep sight of the future she desperately wanted to inhabit. I didn’t want the car afterwards. It felt like a taunt. But I’d think of how much she’d wanted me to enjoy what she hadn’t, and I’d take it for a spin. I sold it later before finally leaving Florida; it had no place in Europe, where I was headed, then New York, where I sought my former life. I felt guilty, but it had been her dream.

Cassadaga was called the leading spiritualist center of the South when I was young. Then it was a backwater central Florida small town full of mystics and mediums, not far from a nudist colony where older couples played tennis naked except for their white socks and shoes. I drove into the colony once by mistake. I’ll never forget it. Some of the couples wore white visors. This was all part of the realer Florida, one I’ve come to appreciate. It included Weeki Wachee, where women dressed in mermaid’s outfits would perform underwater for an audience in a glass-bottom boats.

My father, a pediatrician and a rationalist, would semi-mock me when he learned I’d gone to Cassadaga again. He was born in Haiti; his mother was a Catholic who didn’t completely dismiss Voudon, the indigenous religion that many Haitians live by. She was superstitious and liked to hedge her bets. If the Haitian saints were in the bardo, ready to assist, why not direct your prayers to them too, not just the Catholic Virgin, her favorite spiritual aide? My father was an agnostic. But I know he understood why I’d take the MGB and disappear. It was my passage through the looking glass.

We had another person with us sometimes, a guy I was trying half-heartedly to date because I was still fighting my sexuality in order to hold onto my father, who was forbidding about gay people. I may as well be dead, he’d told me more than once, about my lesbianism. He meant it. Yet he loved me deeply, and my being gay added to his heartbreak. He’d been raised to fear gay people; he worried I’d be socially outcast, and he would, too. So, I held onto his conditional love during my limbo in Florida, needing my family more. I thought then that my non-boyfriend was maybe gay; he was slightly pigeon-toed, with a girl butt. He naturally swished when he walked. Those were things I liked about him, plus his very kind eyes. He was a good listener. I don’t know what his heartbreak was. Maybe the closet? He and Brooke were my ballast.

I met her at the local NBC television affiliate in Daytona Beach, still thinking I had a future career in television. I’d done a stint for a major documentary show in New York but left the minute my mother was given a month to live. She lasted six. We found out the day of my college graduation. I couldn’t think about the future when my present was imperiled.

Brooke had snagged a job, like me, operating one of two big TV cameras. We had to film a cable fishing show at 5 a.m. The fishing show was like a block of cement on my heart and mind: I truly thought I could sink no further. Time was relentlessly deadly; I felt like screaming sometimes behind the camera I was so insanely bored. By the time the clock would strike 5:59, Brooke and I would tear out of the station, hop in my car, and take off for the orange groves by Cassadaga. We would play Linda Ronstandt’s one sort of rock and roll album at the highest volume and on repeat. The flat, straight, highway leading toward Cassadaga would shimmer with rising heat. I’d let myself sing, loudly, and explode with everything that needed release, imagining my mother’s hands of the wheel, remembering how she loved to shift gears and race the engine of the feisty Peugeot she and my father had once ordered from France. She loved driving the nervous car and I loved seeing her happy.

We would pass Eatonville, where Zora Neale Hurston had lived and wrote about her community of poor, Black Floridians. I only later read her books. I knew Hurston as an American Black woman who had written about voudon, and her novel, Tell My Horse. I knew the famous white anthropologist-dancer Maya Deren had a made a film based on it. I’d sometimes slow the car down, slip over to the backstreets of sleepy Eatonville. Occasionally, men and women sitting on a porch in front of their small wooden houses would wave hello. Later I learned Zora was bisexual. There’s a museum there now about her life; every year Zora scholars flood the town to celebrate her. She’s a queer lit and Harlem Renaissance icon.

In Cassadaga, I’d go to see Ms. Bobby, who lived in a white trailer with her husband, surrounded by orange trees. She read cards or palms. She once told me I’d one day live in San Francisco, and lo and behold, she was right. Maybe she knew I was queer; it was written all over me, and that was just an easy guess. I wonder. She also said my father might live in Seattle, and that was wrong. She told me other things that were later right, though. Much later, I went back there, and Ms. Bobby was gone. She’d died of cancer. I remember thinking, wait, wouldn’t she have known about it way beforehand? But it’s a truism that we can have insights about others and be blinded to ourselves.

That fall, I moonlighted at a motel on the beach. It also perfectly matched the sharp flat edge of my grief. I gave out keys out late at night, ate meals at the Denny’s nearby. I read in a folding beach chair between customers. I also made two major discoveries that saved me. One was the biography of Joe Orton by John Lahr, Prick Up Your Ears, which details the British gay trickster playwright and novelist Joe Orton’s life and his murder by his lover, John Halliwell. John, driven by jealousy of Orton’s fame and promiscuous affairs, it seems, killed Orton with a hammer, then killed himself. Their story was later made into a movie by Stephen Frears. What saved me was reading about Orton’s life in London, the books and the gay society he inhabited. He was funny and his social commentary was scathing. But it was his diaries that spoke to me: vulnerable, revealing his creative struggles.

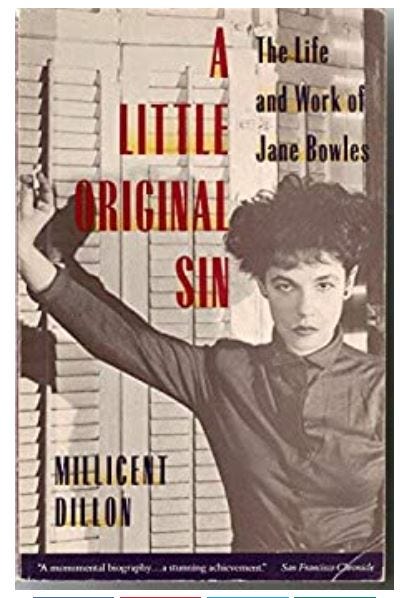

I also discovered another biography that I read like a bible, A Litte Original Sin, by Millicent Dillon. It remains my favorite biography, ever. It’s a masterful portrait of a very flawed American playwright and writer and depressive, Jane Bowles, and her expat life in Tangiers with her husband, the more famous Paul Bowles. He was a talented writer and musician; I do love his books. They were both queer, obviously both bi though Jane is often called a lesbian and Paul, a gay man. Their life was, like Orton’s, a larger-than-literary-life, full of adventure and drunken parties and passion and betrayals. They had talented, sloppy friends.

Their lives represented an escape for me, a looking-glass mirror to glimpse on what one might want; at least it offered a direction. They were very flawed and problematic, too: Both writers and their partners were narcissistic—all of them, the whole bunch, I felt. The rent boys that Paul Bowles, and Orton and Halliwell, sought out in Morocco and elsewhere revealed an unexamined class and colonial racism. Jane’s relationship to her butch Berber lover, Cherifa, was also problematic, and for other reasons.

Still, the books saved me; their lives were a lifeline. I silently thanked Lahr and Dillon, who I admired as much as their subjects. They helped me see myself again.

Yesterday afternoon, I lit a candle for my friend’s brother, who I never met because of Covid. He was already too sick. I’ve gotten a sense of him through my friend, who would’ve switched roles with her brother in an instant and agonized that she couldn’t. He was leaving small children behind—more cruelty. His spouse must bear not only her grief, but theirs, all after the worst of limbo-land. So does my friend. She’s been a devoted auntie.

I know the heartbreak won’t end easily or quickly now, either. I want to tell her about how it was an instant passage for me, when I read her text, to be seated back in the car, remembering the heat rising, and Brooke’s face in profile, as we drove past cow pastures, with Linda’s plaintive voice filling our ears. I could feel the humid air, the fresh-cut grass. It’s just all there, still. I’ll never leave that car, that’s the truth. She’ll have her brother inside her, inside every memory of their life, which is her life, and every time something randomly reminds her of something about their shared life, she’ll feel it and maybe be able to see him.

Or at least, I hope she will. I could. I could see through my mother’s eyes, driving into the blinding backwater Florida mornings, the horizon a flat line of trees, passing an occasional gas station or a roadside fruit stand where we’d stop to buy navel oranges. I’d suck them loudly and throw the remains into the fields for the birds, knowing it would sweeten their day, too.