Unfinished Business: A Spotlight Conversation with lesbian feminist scholar-turned-anti-racist activist Jessie Daniels (Part 1 of 2)

A deep dive into whiteness, wokeness, and the unfinished business of tilling America’s racist soil-- and why public sociology turns her on.

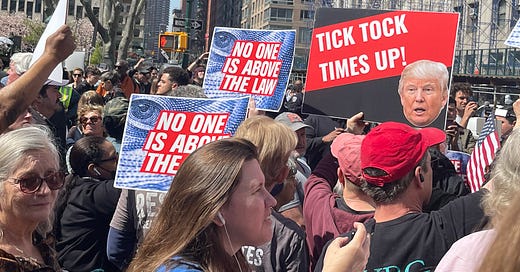

New Yorkers Greeting Donald Trump at the downtown Manhattan courthouse, April 4, 2023.

Photo: AC d’Adesky.

I was walking around all day with a smile on my face last Tuesday, April 4th, now enshrined as a new day in American history. That’s when Donald J. Trump, a buffoon ex-president to us progressives and a would-be Messiah to MAGAland, was finally arrested for one of his too-many-to-be-named crimes. This one felt smaller, by comparison to the failed January 6 coup, it’s true. Trump is charged with cooking his presidential campaign books to mask a $130,000 payoff to the stripper Stormy Daniels as a legit legal expense. That isn’t the only payoff either; he also paid off a hotel doorman with loose lips who threatened to spill the beans on a possible illegit child Trump may have fathered outside of his wedlock to Melania, who was busy nursing Barron when Trump hooked up with Stormy. The bastard child story is supposedly not true, because the lying tabloid owner who helped Trump pay Stormy off looked into it and says so (do you believe them?) but if that later proves a fresh scandal, don’t be surprised. As it stands, there’s little in our fetid empire these days that can compete with the made-for-tabloid-rabid TV spectacle of Trump’s legal woes.

I mean, c’mon. Stormy Daniels has nicknamed her breasts Thunder and Lightning. Is there a greater American political story than this one? No, and it’s really a pity the great New Journalism novelist Tom Wolfe, who so well captured America’s sordid 1960s political underbelly in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, isn’t with us still to skewer Donald and his merry MAGA minions. I’m sure Tom would’ve trained his satirical eye on Stormy Daniels as some sort of modern American Madonna, if not a saint. The fallen woman, now rising high in the hopeful eyes of America’s democrats. It’s such a juicy story

That’s why I was smiling all day last Tuesday, and I wasn’t alone. All across the land and world, everyone who feels like Trump has dragged our nation down by a heavy, dirty anchor, felt a little happier. That includes Jessie Daniels, who I spoke to by Zoom that same Tuesday afternoon.

It’s funny you should ask me that, she says. I kind of have a skip in my step today. It’s partly the glorious weather but also…many of us have been saying that this Queens man has been committing crimes in public, in plain view, for decades now…so as conflicted as I am about the legal system, it’s good to see him being brought to justice.

I tell her I was at the courthouse for what felt like a necessary date with history, not because I’m convinced Trump will be convicted, even though everyone knows he’s guilty as hell (just look at how Melania is treating him, totally ignoring her husband, not even showing up to symbolically support him)but to be among friends, to stand with Rise and Resist, who include old-time activist pals from 90s Act Up and the Lesbian Avengers. Rise and Resist formed to dog Trump when he was first elected. Group members were holding a long black banner near the courthouse, with white words and the stark message The Time Is Now, and holding court for a phalanx of press and smart phone citizen-journalists.

The media had swarmed to watch Trump arrive in a line of black limousines, escorted by Secret Service officers in Men in Black sunglasses, unsmiling. They made me cheer, too. I kept seeing copycat Agent Smiths from The Matrix. Further up the street, Trump supporters shouted at our side, separated by a line of cops. All of it cheered me up, the whole scene. The sun was shining through the clouds.

I’m sure you or some of our friends down in the crowd were also blowing whistles at Marjorie Taylor-Greene when she tried to get out of her vehicle and give a speech about all the stuff that was going on, Jessie continued. I thought it was just such a great example of the kind of activism for when these kinds of people show up in the street. It’s not a question of shouting them down, but there are ways to push back on them. People just had regular whistles and were blowing them and she couldn’t be heard over them. So, I thought it was a great action.

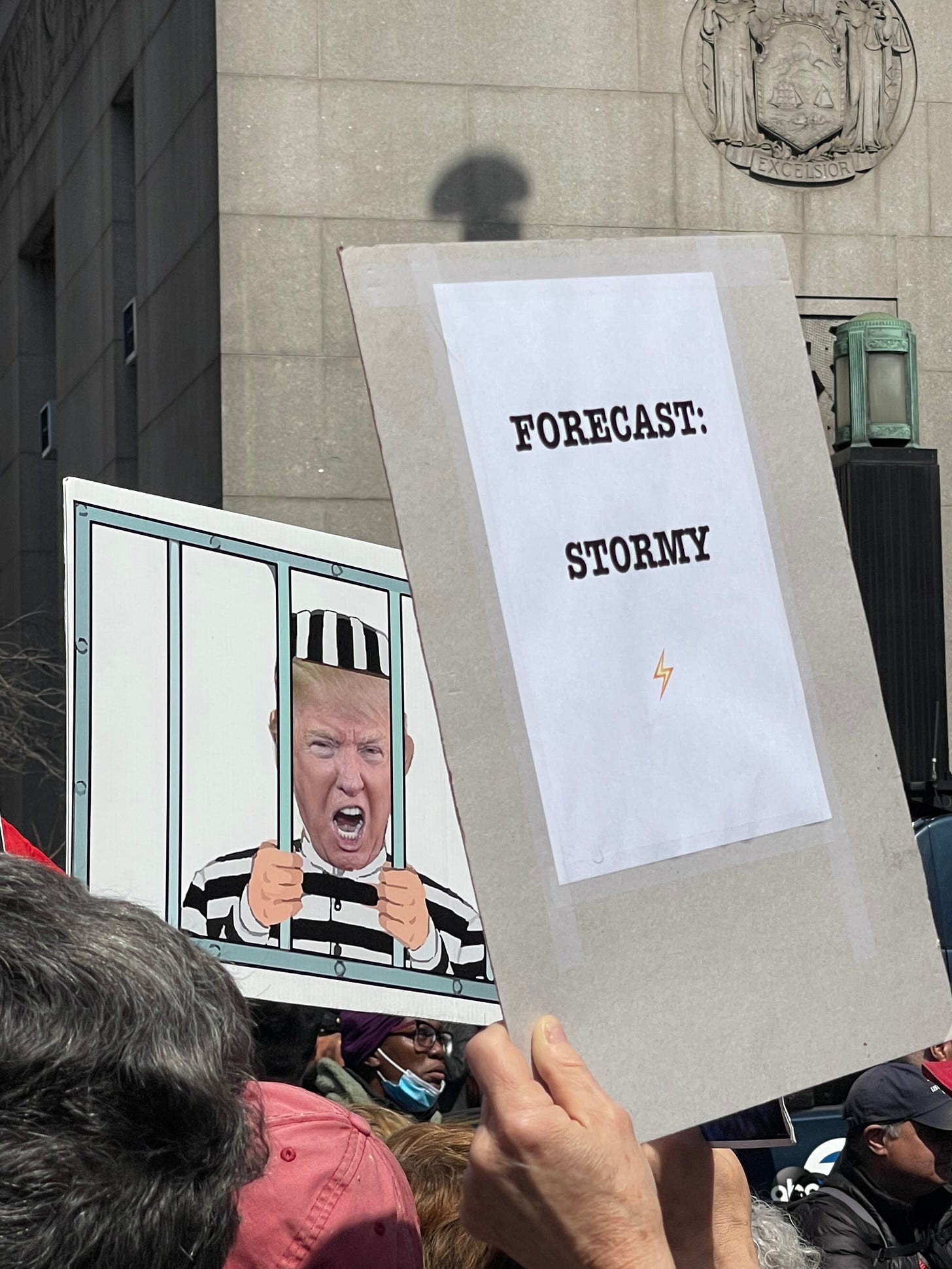

Stormy weather ahead for The Donald. Photo: AC d’Adesky. April 4, 2023.

For those of you who don’t know, Jessie Daniels is not directly related to Stormy, but considers her a spiritual cousin. Jessie is a public sociologist and professor at Hunter College, and the Director of their Master’s Program in Applied Digital Sociology. She’s a proud dyke, a white feminist and anti-racist activist, and author of several books on embedded and internet racism in America. Her early books include White Lies (Routledge, 1997) and Cyber Racism (Rowman & Littlefield, 2009), which also explored her interest in digital media technology, including cyber hate. Her latest book, Nice White Ladies: The Truth About White Supremacy, Our Role in It, and How We Can Help Dismantle It, which takes on the ‘Karens’ phenomenon and so much more white lady ugliness.

In it, she removes her own former white southern lady gloves to “reach beyond the strictures of niceness and the constraints of ladyhood” and “dismantle the systemic racism they have upheld.” I’m quoting from the book jacket PR there. The book blends archival scholarship, reporting and personal memoir, including details of her grandfather’s membership in the Ku Klux Klan, to talk about how white women have “instigated, encouraged, and benefited from white supremacy.” Her books are a call to arms to divest from white spaces and acknowledge and repair harm. My emphasis added.

Who better, then, to chat about Trump and Stormy Daniels and the unfinished project of white supremacy in America now? Jessie has gone deep into the Trump presidency, finding it all fertile terrain to explore the intersection of whiteness and gender and politics. As we chat, I can tell she’s also having a blast, while aiming her activist-scholar big guns at the rot.

But first, Stormy Daniels, who was born in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where Trump is popular. What do you think of her? I asked Jessie. Isn’t she a wonderful sort of symbol/figurehead for American politics now? She’s so relatable to MAGAland, I add.

I didn’t know she’d named her breasts, Jessie tells me, laughing. That’s a wonderful tidbit. But her performance of femininity…that’s the Southern part you’re picking up on -- it’s the hair, the dress, the figure, all that stuff…. I joked several years ago when she first appeared that I hoped we are cousins, which is a joke on several levels because, of course, Stormy Daniels is not her given name – she chose that name -- and Jessie Daniels is not my given name -- it’s a name that I chose. I legally changed it, in ‘94. (She changed her name to distance herself from her family’s legacy of white supremacy and to honor Jessie Daniel Ames, a Texas woman who started the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching). So, in a way I do see her as a kind of cousin, pushing back in different ways on Donald Trump. I’ve been cheering Stormy Daniels for several years now. I think she has been badly treated, first by the public, second by Donald Trump. And that’s consistent with how women who speak up are treated in this culture.

Amen, I want to say, in part because I know Jessie is familiar with the refrain of an amen after one reveals a truth or bold statement. She’s an ex-Jesus-Loves-you Bible thumper, one who made her own escape from the deep red region of rural Texas and Christianity, to her current home in liberal, diverse East Harlem. She lives with her honey Amanda Lugg, a Black-British spitfire feminist activist and ex-Act Upper who was born in England. Jessie’s journey, with its share of unexpected turns, is part of the reason her examination of white lady complaint and privilege is sharp, nuanced and enlightening: she’s lived this story, and she’s not looking down from some righteous up above. She understands the nice white ladies, including cousin Stormy and Marjorie Taylor Green, a former fitness enthusiast from Georgia. She brings compassion to her lens, and that makes a difference. They’re her people, or were.

Jessie’s been working for years to unpack own learned inner racism, and that work infuses her scholarship and current activism. Or as she likes to say, the intersection of the personal and the professional. When she talks to fellow white liberals and lefties about their unexamined racist crap, she’s speaking from a personal place of having walked her walk to unpack it, an ongoing journey. These days, she’s found a new political home at SURJ, short for Showing Up for Racial Justice, a national organization with 200 chapters across the US. It organizes white people to fight racial and economic racism and join multi-racial communities. Jessie loves the role-playing exercises the group does; they help her in her work, talking to students and white audiences. Last week, she was in Atlanta, meeting with grassroots activists. Before that, she was warning UN experts about internet manifestations of racism.

More than ever, the personal and professional threads of her life overlap and enrich each other. She wears her activist hat proudly now, but it wasn’t always so.

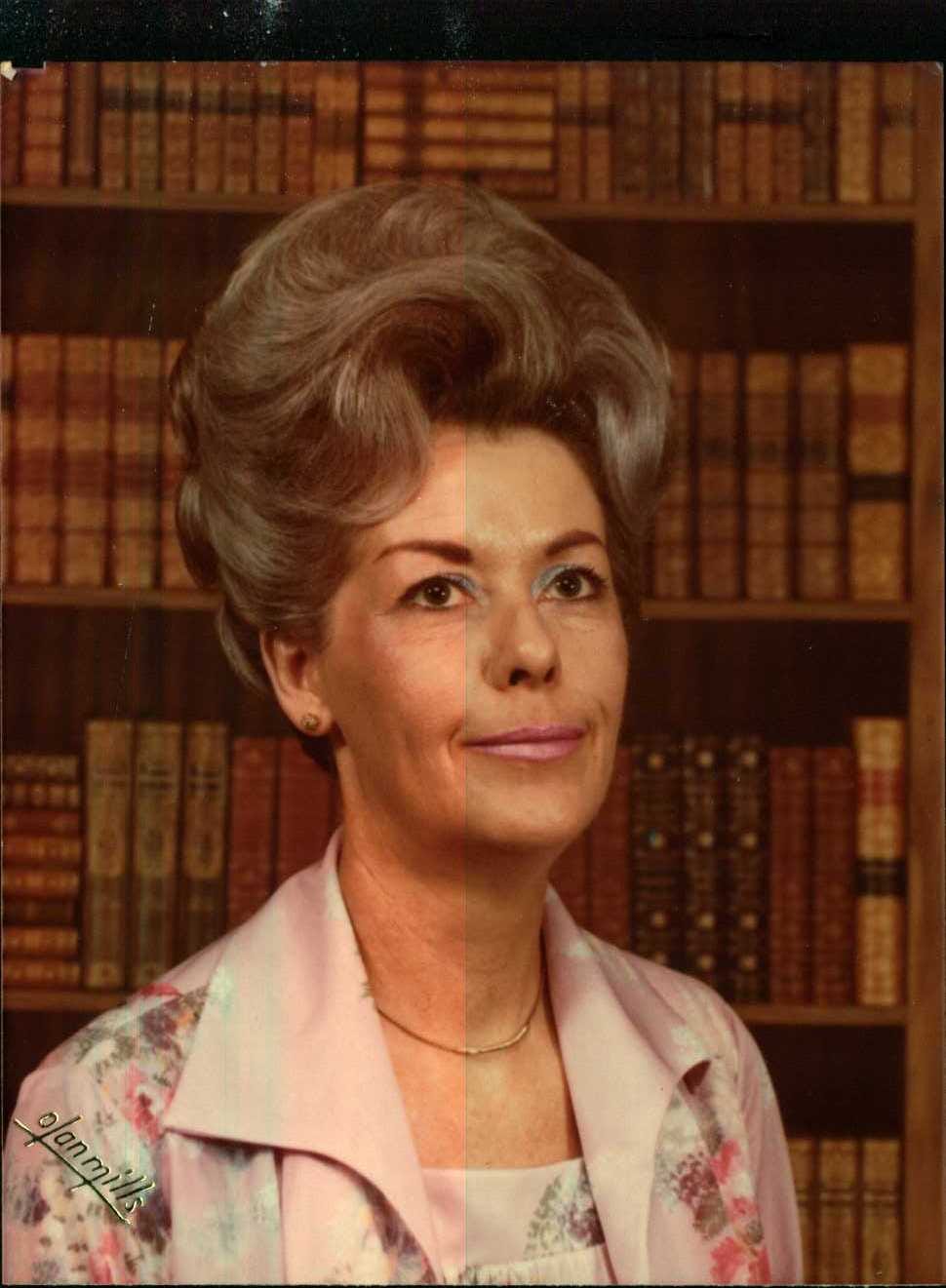

Young Jessie, already eyeing the nice Southern ladies….

Photo: Jessie Daniels personal archive.

Moving from Red to Blue

Jessie was born in Houston in 1961, and lived there until her family moved to Corpus Christi, a few hundred miles south on the Gulf Coast. Her father was a hard-working independent oil-and-gasman who worked as an engineer but hadn’t finished college; he picked a fight with someone and quit school instead. Her mother was a homemaker, one who loved reading and introduced young Jessie to the local library, her childhood second home. Jessie describes her family as coming from a mixed class background. My father was more middle-class and had aspirations to the upper-middle-class, she explains. My mother and her family were dirt poor, like literally had to scratch a living out of central Texas farmland.

Her parents had both married other people before her birth. She has two older half-brothers who weren’t around as she grew up. It was a little like being raised as an only child but also with these phantom brothers, she explains. She was close to her parents, especially because there weren’t a whole lot of other people around later. She’s also a proud Texan, more for its blue stripes than big red stripe. I think there are a lot of cool things about being from Texas, she adds. There is a whole strain of progressive resistance in Texas going back to people like J. Frank Dobie and Molly Ivins, who were both writers, and people like Elvia Perez, one of the activists that led a Chicano uprising in Uvalde schools in 1970s, who really inspire me. That is the part of the tradition of Texas that I love and hold onto. Later in college, she discovered the great activist Ida B. Wells.

Growing up in South Texas as part of an Anglo ‘minority’ had a profound impact. When I ask what values she took from her family, she says, there was always a sense of adventure, my father especially. He would drive the family across the border every three or four weeks. My father, who was weirdly racist in a lot of ways, had a deep affinity for Mexican people, for Mexico as a country, Jessie explains. When we would cross the border, he would sigh in relief and go, ‘ah, home again.’ For Jessie, the trips provided a very early understanding that borders were bullshit. And I was really struck by the poverty, and my parents’ indifference to it.

Her father also liked to claim Cherokee roots, a bit of wishful untruth that GOP fabulist George Santos might appreciate. (Santos, a Catholic, has claimed Jewish roots, and also loves Indigenous people). Santos also turned up for his media moment in the sun Tuesday at the Trump arraignment. Jessie thinks the Cherokee bit reflects her father’s sense of spiritual connection with Indigenous culture, however misplaced. Growing up, she and her dad would talk late into the night about current affairs while he tinkered, taking something apart to rebuild it. Jessie traces her love of technology and deep discussion to those moments.

Jessie’s Mama, hair piled high like a Texan belle. Photo: Jessie Daniels personal archive.

Her mother was a different creature, regal in appearance, tall with swept up hair, one who cared about appearances. She struggled with chronic depression and felt isolated from others, with few friends. Jessie lost her mother early, at the tender age of 21, to suicide. She discusses her mother and that tragic chapter in her recent book, a death that was a harbinger of the current trend in ‘deaths of despair’ among middle-aged white women.

Her parents weren’t political, she says. I never saw my parents vote ever, or politics as a thing we could be engaged in, Jessie says. They did have a strong antipathy to Kennedy and Johnson, which are some of my earliest memories. They didn’t like Kennedy because he was liberal; there was extra antipathy for Johnson because he came from Texas and had done all this stuff for civil rights. She explains that her grandfather had worked for a political candidate who’d lost to Johnson by 85 votes. She’d been told the winning margin was all dead people who voted in alphabetical order. Adds Jessie: There was a sense that Johnson was an illegitimate president but also that they were all illegitimate. All, meaning all politicians. Her father had a classic conservative outsider’s suspicion of Washington, including corporate lobbyists and Big Oil.

From Tomboy to Bride of Jesus

I was kind of weird mix of a tomboy. I had a minibike and was out all summer; it was the other boys who wanted to play with the minibike. But I also liked high femme stuff and getting all dolled up. We’re talking about what life was like for young Jessie, and when she first had an inkling of being different from the other girls. It wasn’t right away.

I worked very hard to ignore issues of sexuality as a young person, especially growing up in Texas, Jessie recalls. I had intense friendships with other girls but had no language for it. Instead, she dated boys, and got married young, at 19, to a Christian prayer group song leader. I am embarrassed to tell you I chose the college because of a prayer group that was meeting there, she says, laughing. By then, she’d also married Jesus, or was trying to.

My parents were not at all religious; I refer to them as worshipping at the church of the Bloody Mary brunch, she says. But they would take me to church to be with other people and my kind of gestalt was having crushed on people who kind of came from religious homes. I would go from Catholic to Methodist to whatever the person I was crushed out on was doing and follow their lead. It speaks to a real desire for boundaries and community in my life, she notes.

At 15, the first of two life-shifting events occurred. The first took her into the church; the second took her back out. Jessie’s father was badly burned in a terrible industrial accident when a gas compressor he was working on blew up; the third-degree burns covered almost 80 percent of his body. He then had what teenage Jessie considered to be a miraculous recovery when, against all odds, his skin grew back. To Jessie, it was divine intervention. From that I got clearly very Christiany and religious, she explains. That’s how she chose her first small college, Stephen F. Austin State University, named after a Texas settler pioneer, in the then-tiny city of Nacogdoches, a name derived from the indigenous Caddo people.

A devout Jessie in 1979, in Nacogdoches, Texas. Photo: Jessie Daniels personal archive.

Jessie was so taken by the spirit that she dropped out of college, at 18, to teach the kids of her church community in a one-room schoolhouse. She also got her first taste of organizing there, working to establish a food coop and bring in organic food. She was deep in the scene, married to the church song leader, when tragedy number two hit. She’d gone back in college in 1982 when her mother drank a fifth of vodka and took five bottles of pills. Her suicide shook Jessie’s faith. It was a moment that I realized this church and this religion I had adopted had no answers for me. And it was also this moment where I was just like, ‘oh, and I’m done with this marriage.’

After that, everything changed, she says. That summer, she took her first women’s studies course, discovered gender and feminism, and later, tackled racism. All of it soon came together in sociology.

Jessie today: the scholar-turned-activist. Photo: Jessie Daniels personal archive.

[END OF PART 1. TO READ PART 2, GO TO MAIN SUBSTACK PAGE OF Tell Me Everything]

To learn more:

https://www.jessiedaniels.net/

Jessie’s SubStack, Jessie Daniel’s Newsletter

Anne Dadesky is the most dishonest person. In 2011, Anne Dadesky called the Child Protective Services to take my daughter from me. From 2005-2011, Dadesky called CPS and seriously alienated my child so that my daughter would hate me. Anne took her ex to court and did the same thing. How ironic! I may have made serious mistakes, and my imperfections hurt my daughter. My daughter was hurt by Dadesky's parental alienation. Since Dadesky used CPS aggressively to alienate my daughter, I have gone to undergrad, and I am in grad school. I learned from my mistakes. My daughter and I will never see each other again. I empathize with my daughter and want to reunite with her. Dadesky blames my daughter for Dadesky's alienation. Should a parent who has completely changed her life suffer the loss of the once-loving bond that she and her daughter once had? I do not know why people are so cruel.